On Jackie Robinson Day: A celebration of something MLB wants left unsaid

The simple son asks, "What is this?"

I don’t want to write pieces that come from the part of my chest that tightens and fills with the bile from my stomach when I feel indignation. No matter how righteous, I want to avoid going to that well. I don’t want to spend time putting together pieces to show how clever I can be when wagging my finger. To put it in baseball terms, I don’t want to write – and you don’t want to read – Earl Weaver’s Airing of Grievances.

I don’t want to be a scold. But Major League Baseball deserves scolding for everything left unsaid.

On Tuesday, the league celebrated Jackie Robinson Day, an annual honoring of the legacy and career of the Brooklyn Dodgers infielder. And if you read the background section in MLB’s press release on Monday, that is all you would know about why he was worth commemorating:

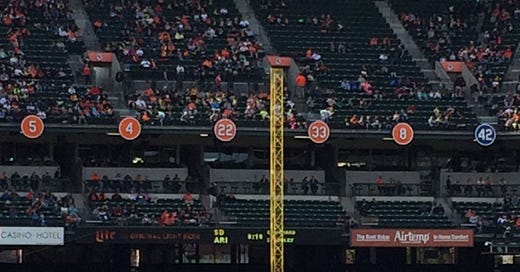

Robinson played his first Major League game at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947, as a first baseman for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Major League Baseball has celebrated Jackie Robinson’s legacy in an extensive and unified League-wide show of support over the years, including retiring his number throughout the Majors in 1997, dedicating April 15th as Jackie Robinson Day each year since 2004, and requesting that every player and all on-field personnel wear his Number 42 during games scheduled on Jackie Robinson Day since 2009.

There are no faults in this statement. Nothing is out of place. Those are events that happened and led to this year’s celebration.

What is left unsaid is everything MLB thinks you already know and therefore do not need reminding about, even as they are holding a league-wide celebration to remind you about a 28-year-old rookie’s big league debut. You know about it, so the league can just mention his name like it’s a promo code and move on.

The league’s website for Jackie Robinson Day adds a bit more context: He “broke Baseball's color barrier when he made his historic MLB debut.”

The phrase “color barrier” is just perfect for them. It says everything you already know and therefore do not need reminding about, that Robinson was Black, and baseball before him was played exclusively by whites.

Plus, “color barrier” has the added benefit that it makes it sound like the reason Black people did not play in the National and American Leagues before the 1947 season was a matter of their failure to overcome obstacles, as if their exclusion was their own doing.

Everyone responsible for maintaining the unwritten, gentleman’s agreement – “a grapevine understanding or subterranean rule” – to keep the game segregated from the owners to baseball’s first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, can be tucked behind the barrier.

The message of Tuesday can be that baseball just happened to be this way until Jackie Robinson arrived, and it wasn’t and isn’t that grand? What a legacy!

That first segment from this year’s press release on Jackie Robinson Day reads the same as the releases from 2019, 2021, 2023, and 2024. Only the final line has changed.

The 2019 version concluded with this line: “Major League Baseball aims to educate all fans about Jackie Robinson, his life’s accomplishments and his legacy.”

The versions for 2021, 2023, and 2024 changed the last line slightly: “... his life’s accomplishments and legacy, while spearheading initiatives that support communities and meaningfully address diversity and inclusion at all levels of our sport.”

The 2025 version changed again: “... his life’s accomplishments and legacy, while communicating his message at all levels of the sport.”

Communicating Robinson’s message is in, and addressing diversity and inclusion is out. What exactly the message the league wants communicated is left unsaid. Gentlemen can surely agree as to what the league means.

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred’s words have changed, too.

“When Jackie took the field at Ebbets Field in 1947, he faced racism and bigotry, but he began a process that integrated our game and led us to the diversity we enjoy today,” he said in 2015.

“Jackie showed the world that equality should be a fundamental right for all and that real change in our society was possible,” Manfred said in 2022. “Baseball did not truly become the national pastime until Jackie – and those who followed him – integrated our sport.”

He added, “On and off the field, baseball seeks to be representative of Americans from all walks of life. We must continually strive to be inclusive and to make diversity not just a business objective, but instead, part of who we are. Our diversity is what makes us great as a nation and as a sport.”

“I think Jackie Robinson transcends any debate that’s going on in today’s society about issues surrounding [diversity, equity, and inclusion],” Manfred said in an interview three weeks ago. “What Jackie Robinson stands for was moving us past an overt kind of segregation that I don’t believe anybody actually supports today.”

MLB wants a celebration, not an examination. So they get a day lousy with backpatting, fans standing to applaud when told to stand and applaud, and no room for giving answers to uncomfortable questions.

Jackie Robinson played for Brooklyn on April 15, 1947, and went 0-for-3 with a run scored. Don’t ask much about what came next.

Don’t look into why the team in The Bronx waited another eight years – playing 1,233 regular season games in the meantime – before Elston Howard played in the second game of the 1955 season to make the Yankees the 13th of 16 clubs to integrate.

Don’t ask why the Boston Red Sox (a franchise that held a sham tryout for Robinson and two other Black players in 1945) have the distinct shame of being the last team to maintain their discriminatory policy before Pumpsie Green appeared on July 21, 1959, 12 years – and 1,946 regular-season games – later.

Don’t check the date of MLB’s first black manager.

Don’t reflect on Robinson’s legacy and conclude what Kareem Abdul-Jabbar did when he said this week: “Jackie had an idea of what we had to confront. We had to confront segregation. In many ways, we’re still confronting it. But it’s worth it. It certainly makes people respect us as a country when they see there is some tension there. And good people are trying to do the right thing.”

Ignore the part about how Tuesday marked 78 years to the day since a man – born into a family of Georgia sharecroppers, the grandson of a slave, who served in a segregated U.S. Army unit during World War II and was almost court-martialed for refusing to move to the back of a bus – ended baseball’s all-white era for good, 62 years, 7 months, 11 days after Moses Fleetwood Walker played his final game for the Toledo Blue Stockings.

The intervening period contained the careers of Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson, the first five members of Baseball's Hall of Fame. Nap Lajoie, Tris Speaker, and Cy Young, George Sisler, Lou Gehrig, and Rogers Hornsby, too. Eddie Collins played, retired, entered Cooperstown, and was the Red Sox general manager in 1945. Even Kenesaw Mountain Landis was enshrined soon after his death in 1944.

The careers of John Henry Lloyd, Martin Dihigo, Oscar Charleston, Judy Johnson, Cool Papa Bell, and Josh Gibson came and went during those 62 years, 7 months, 11 days, too.

They aren’t as familiar to most baseball fans. MLB can’t just say their name, and you already know and therefore do not need reminding about why they are significant.

Baseball did induct them in the Hall of Fame in the 1970s, recongied the seven Negro Leagues as “Majors” on par with the AL and NL in 2020, and incorporated their statistics in their official ledger in 2024. But the barrier kept them out during their playing days. Denying the fame, fortune, and humanity.

“When I look back at what I had to go through in Black baseball,” Robinson wrote in his autobiography, “I Never Had It Made.” “I can only marvel at the many Black players who stuck it out for years in the Jim Crow leagues because they had nowhere else to go.”

But if you are explaining and educating, you are not celebrating. So do not ask about them, either.

Has MLB or the commissioner’s office ever formally apologized for the “subterranean rule” that kept baseball segregated?

In fact, it would be better if you did not ask any questions beyond the simple one: “What is this?”

It is Jackie Robinson Day, the end, play ball!

Ben Krimmel is a writer from Baltimore who lives and works in New York.